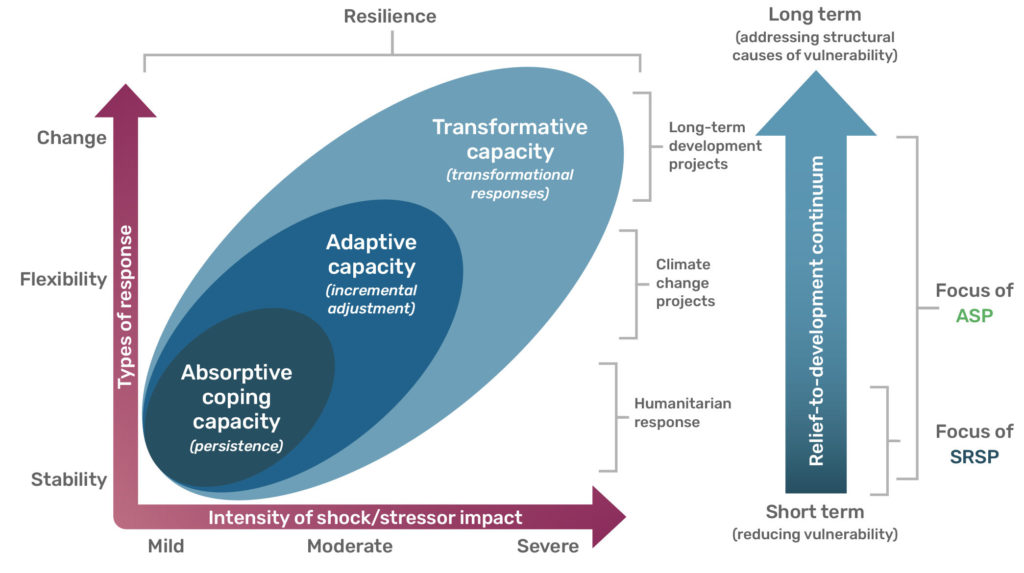

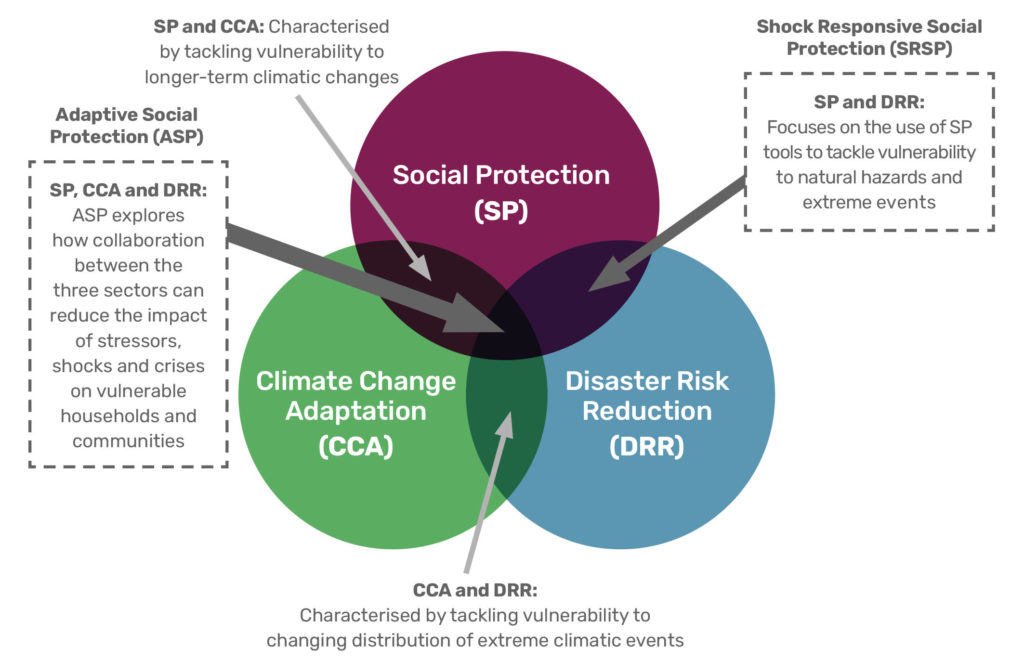

Social protection, climate change adaptation (CCA) and disaster risk reduction (DRR) all share the same motivating principle of seeking to mitigate risks, reduce vulnerability and build resilience to livelihood shocks (Vincent & Cull, 2012). This overlap lends itself to integrated policies and programmes which address both social and environmental factors, with a long-term, preventative approach. This is known as ‘adaptive social protection’. While some use the terms ‘adaptive social protection’ and ‘shock-responsive social protection’ interchangeably, adaptive was first used by Davies et al. (2009: 9) to refer to transforming productive livelihoods to adapt ‘to changing climate conditions rather than simply reinforcing coping mechanisms’. Work by Cornelius et al. (2018) sets out how the two concepts differ – see Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4. Thematic positioning

Source: Cornelius et al. (2018), reproduced with permission.

Figure 5. ASP and SRSP in the context of resilience and the development continuum

Source: Cornelius et al. (2018), reproduced with permission.

As well as helping to protect against current shocks, ‘social protection can support more effective resilience building at scale by integrating early action and preparedness’ (Costella et al., 2017: 31). For example, public works programmes may contribute to adaptation and DRR through the construction of community assets that enhance resilience through better natural resource management and adaptation. Adaptive social protection could be used to target those whose livelihoods and status are vulnerable to climate change, reducing their dependence on climate-sensitive livelihoods strategies, and helping build household resilience to climate risks (Davies et al., 2009).

The evidence that social protection can effectively reduce vulnerability to climate change is still quite thin, but is increasing (Vincent & Cull, 2012). Much ‘“climate-smart” social protection has focused on the ability of [social protection] to support shock response’, with more limited experiences of ‘the role it can play to anticipate and adapt to climate risks’ (Costella et al., 2017: 32; Vincent & Cull, 2012).

Key factors to consider to ensure social protection programmes are more ‘adaptive’ and able to respond to increasing risks posed by climate extremes and disasters include: ‘designing flexible and scalable programmes, ensuring the support provided reduces current as well as future vulnerability and putting in place targeting, financing and coordination mechanisms that facilitate cross-sector responses to different types of risks’ (Ulrichs, 2016: 12).

Key texts

Costella, C., Jaime, C., Arrighi, J., Coughlan de Perez, E., Suarez, P., & van Aalst, M. (2017). Scalable and sustainable: How to build anticipatory capacity into social protection systems. IDS Bulletin 48(4).

This article argues that scalable social protection systems can support climate risk management by focusing on risk mitigation and preparedness measures that increase the capacity of the system to anticipate shocks. It focuses on Forecast-based Financing (FbF), an innovative instrument being piloted as part of humanitarian operations to support improved anticipation and mitigation of climate shocks.

Ulrichs, M. (2016). Increasing people’s resilience through social protection (Resilience Intel 3). BRACED.

Ulrichs identifies critical design factors that support the role of social protection in increasing vulnerable people’s ability to anticipate, absorb and adapt to climate shocks and disasters. These include the adequacy of support (sufficient size and type of transfer, delivered in a reliable and timely manner), as well as flexibility of social protection programmes’ design and implementation mechanisms to expand coverage during times of crisis (and to scale down afterwards). Other factors are adequate information management systems, appropriate financing mechanisms and cross-sector collaboration.

Davies, M., Guenther, B., Leavy, J., Mitchell, T., & Tanner, T. (2009). Climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction and social protection: Complementary roles in agriculture and rural growth? (IDS Working Paper 320). Brighton: IDS.

How can synergies between social protection, DRR, and CCA be identified and developed? Social protection initiatives are unlikely to succeed in reducing poverty if they do not consider both the short- and long-term shocks and stresses associated with climate change. The ‘adaptive social protection’ framework helps to identify opportunities for social protection to enhance adaptation, and for social protection programmes to be more climate-resilient. Adaptive social protection involves a long-term perspective that considers the changing nature of climate-related shocks and stresses, draws on rights, and aims to transform livelihoods.

See also:

Bene, C., Cornelius, A., & Howland, F. (2018). Bridging humanitarian responses and long-term development through transformative changes – Some initial reflections from the World Bank’s Adaptive Social Protection Program in the Sahel. Sustainability 10(6), 1697.

Ziegler, S. (2016). Adaptive social protection – Linking social protection and climate change adaptation (GIZ Discussion Papers on Social Protection). Bonn & Eschborn: GIZ.

Wallis, C., & Buckle, F. (2016). Social protection and climate resilience: Learning notes on how social protection builds climate resilience. Evidence on Demand, UK.

Other resources

Article/blog: Cornelius, A., Béné, C., & Howland, F. (2018). Is my social protection programme ‘shock-responsive’ or ‘adaptive’? Itad.

Article/blog: Cornelius, A., Béné, C., Howland, F., & Henderson, E. (2018). Five key principles for adaptive social protection programming. Itad.