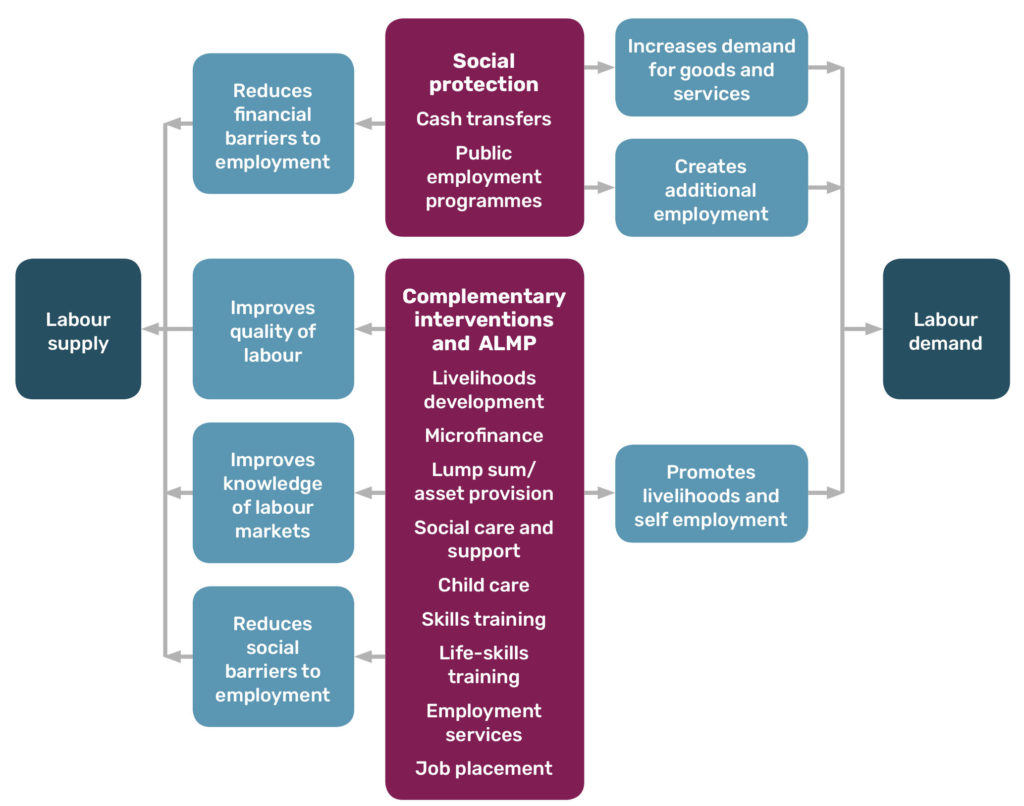

Social protection impacts on employment through various channels. Figure 6. provides a summary of supply- and demand-side labour effects.

Figure 6. Social protection impacts on labour demand and supply

Note: Public Employment Programmes (PEPs) are ‘programmes creating state sponsored employment which is not market based (known as Public Works Programmes, Workfare, Welfare to Work, Cash for Work, Employment of Last Resort, Employment Guarantee programmes, etc.)’ (McCord, 2018: 10).

Source: McCord (2018: 21), CC BY 3.0 AU licence.

Several reviews highlight there is no evidence of cash and food transfers creating disincentives to work (OECD, 2019; Ralston et al., 2017: 25; Mathers & Slater, 2014: 12). However, in terms of effects on labour, OECD (2019: 50) concludes that ‘[m]odest transfers tend not to be strongly associated with changes in labour supply in either participation or intensity (hours worked). Evidence for the most studied social assistance programmes, conditional and unconditional cash transfers, is mixed’. For example, Bastagli et al. (2016: 9) report: ‘For just over half of studies reporting on adult work, the cash transfer does not have a statistically significant impact on adult work. Among those studies reporting a significant effect among adults of working age, the majority find an increase in work participation and intensity. In the cases where a reduction in work participation or work intensity is reported, these reflect a reduction in participation among the elderly, those caring for dependents [sic.] or are linked to reductions in casual work.’

Looking at the long-term effects for children and young adults in Latin America who benefited from conditional cash transfers in early childhood or during school years, a study by Molina Millán et al. (2019: 119) found mixed employment and earnings impacts, ‘possibly because former beneficiaries were often still too young’.

At the meso level, there is evidence of cash transfers leading to positive impacts on labour markets, through boosting trading activities and local businesses (Bastagli et al., 2016: 29). OECD (2019: 52–53) also finds that conditional cash transfers ‘tend to have positive or no effects on investments in small businesses’, but that they ‘do not seem to impact investments in formal businesses’. The extent of cash transfer multiplier effects depends on whether the transfers are cash or in-kind and can be limited by the often very small size of transfers in many low-income countries (and in particular typical for PWPs) (Mathers & Slaters, 2014: 14).

Looking at other types of interventions, there is no evidence that public works programmes generate medium- to long-term sustainable extra employment, or on what the impacts are from skills developed ‘through training or on-the-job practice’ (GIZ, 2019: 6, 8).

Graduation programmes complement transfers with access to savings and credit, and training and tailored coaching. Long-term evidence on the impacts of graduation programmes is still scarce, including on their labour effects, but is slowly emerging as more longitudinal data becomes available. Evidence of longer-term impact is already available for BRAC’s Targeting the Ultra Poor (TUP) programme, showing that women had diversified livelihoods and increased earnings seven years after programme participation (Bandiera et al., 2016).

Turning to active labour market policies, McKenzie (2017: abstract) cautions that many evaluations find ‘no significant impacts’ on employment or earning. This includes vocational training, wage subsidies, job search assistance, and assistance moving for jobs. McKenzie identifies that urban labour markets ‘appear to work reasonably well in many cases’ and therefore there is ‘less of a role’ for these kinds of interventions (ibid.). Instead, there is more of a need to help firms overcome obstacles in creating more jobs (e.g. training on labour laws and provision of legal support), and to help workers access different labour markets by moving into different sectors and accessing jobs in new locations (ibid.: 17–18). For labour market regulation, there is limited research and from the evidence available, effects are small and mixed. Betcherman (2014: 124) looks at minimum wages and employment protection legislation (EPL) and finds that ‘[e]fficiency effects are found sometimes, but not always, and the effects can be in either direction and are usually modest… youth, women and the less skilled are disproportionately outside the coverage [of this legislation] and its benefits’. Bhorat et al. (2017: 47) find limited research on the employment effect of minimum wages in sub-Saharan Africa, but overall find from Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and South Africa that ‘introducing and raising the minimum wage has a small negative impact or no measurable negative impact’. However, there is significant variation in findings and evidence of employment losses in some countries, in part due to ‘the great variation in the detail of the minimum wage regimes and schedules country by country, but also by the variations in compliance’ (ibid.: 48).

Key texts

See Economic growth – Key texts and additional references:

McKenzie, D. (2017). How effective are active labor market policies in developing countries? A critical review of recent evidence. The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2), 127–154.

Betcherman, G. (2014). Labor market regulations: What do we know about their impacts in developing countries?. The World Bank Research Observer, 30(1), 124–153.

McCord, A. (2012). Skills development as part of social protection programmes. Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2012. London: ODI.

Other resources

Conference/seminar/webinar: Integrating the graduation approach with government social protection and employment generation. (2018). Social Protection for Employment Community. (1h:19)