Coverage and spend

The last 20 years have seen a huge increase in social protection programmes, both in the number of programmes and number of countries with programmes (Gentilini et al., 2014). Much of this expansion is accounted for by social assistance and particularly cash transfer programmes (Bastagli et al., 2016: 5; de Groot et al., 2015: 4).

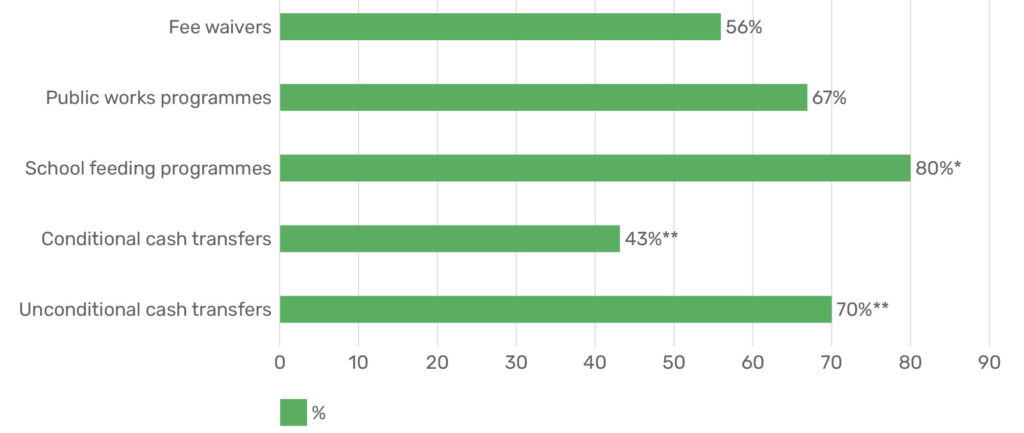

Today, most countries have a diverse set of social assistance programmes. Figure 2 shows percentage of countries with fee waivers, public works programmes, school feeding programmes, and conditional and unconditional cash transfers. In addition to these schemes, an estimated 114 countries have introduced old-age social pensions, the latest by Myanmar in 2017 (HelpAge Social Pensions Database[1]). Growth in programme adoption has been especially high in Africa, where 40 countries out of 48 in sub-Saharan Africa had an unconditional cash transfer (using a definition including social pension[2]) by 2014, double the 2010 total (World Bank, 2015: 7).

Figure 2. Percentage of the ASPIRE[3] database countries with social assistance programmes

Notes:

* Original text states ‘more than 80 per cent’.

** The conditional and unconditional cash transfers are non-contributory schemes. The ASPIRE definition of unconditional cash transfers includes: poverty-targeted cash transfers, last-resort programmes; family, children, orphan allowance, including orphans and vulnerable children benefits; non-contributory funeral grants, burial allowances; emergency cash support, including support to refugees and returning migrants; public charity, including zakat. This category does not include social pensions (World Bank, 2018b: 7).

Social pensions are not included in this figure.

Source: Authors’ own, based on data from World Bank, 2018b: 1.

Globally, low- and middle-income countries spend an average of 1.5% of GDP on social assistance programmes (World Bank, 2018b: 1). There are variances between regions and individual countries: countries spend an average of 2.2% of GDP in Europe and Central Asia, 1.5% in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, 1.1% in East Asia and Pacific, 1.0% in the Middle East and North Africa, and 0.9% in South Asia (ibid.: 16). The prominence of cash transfers in social assistance is also evident in spending patterns. Globally, cash transfers (including unconditional and conditional cash transfers and social pensions) account for more than half of total social assistance spending (ibid.: 27) with many countries spending more on these programmes over time (ibid.: 1).

Looking at broader social protection, pensions for older women and men are the most widespread social protection instrument, with the highest coverage (ILO, 2017: 75). Globally, 68% of people above retirement age receive a pension, either contributory or non-contributory (ibid.). However, there are large regional variations: ‘[C]overage rates in higher income countries are close to 100 per cent, while in sub-Saharan Africa they are only 22.7 per cent, and in Southern Asia 23.6 per cent’ (ibid.: 79).

Old-age social pensions (i.e. non-contributory) have substantially increased in the past two decades: ‘Today almost all Latin American countries have them, whereas Sub-Saharan Africa economies have some of the largest old-age social pensions systems in terms of the share of the elderly population covered’ (World Bank, 2018b: 73).

Other schemes have low coverage globally (e.g. globally, only 21.8% of the unemployed receive unemployment benefits), with wide variations by region and country (e.g. only 5.6% of the unemployed in Africa receive contributory or non-contributory unemployment benefits, compared with 22.5% in Asia) (ILO, 2017: 49).

Gaps

There remain significant gaps in social protection coverage around the world. The ILO (2017: xxix) highlights ‘a significant underinvestment in social protection, particularly in Africa, Asia and the Arab States… Only 45 per cent of the global population are effectively covered by at least one [contributory or non-contributory] social protection benefit, while the remaining 55 per cent – as many as 4 billion people – are left unprotected’ (ibid.: xxix). Looking at contributory and non-contributory programmes, coverage varies by vulnerable group (68% of older people globally are effectively covered by at least one benefit compared to 35% of children and 28% of people with severe disabilities) and by region (only 18% of people in Africa to a high of 84% of people in Europe and Central Asia – excluding health protection which is not covered under SDG indicator 1.3.1) (ibid.:: 167, 123, 158).

For non-contributory social assistance programmes, in low-income countries only 18% of the poorest quintile are reached by social assistance interventions (World Bank, 2018b: 1). Moreover, social assistance schemes in low-income countries only cover a limited proportion of the active population, hindering the potential positive effects on economic development and productivity (ILO, 2017: 123).

Systems

More recently, efforts have focused on building and strengthening integrated and comprehensive social protection systems, moving away from fragmented individual programmes. A social protection system can be considered at three levels: ‘(i) the sector (mandates, policies, regulations etc.); (ii) individual programmes; (iii) delivery [or administrative systems] underpinning the programmes (databases, payment mechanisms, etc.)’ (O’Brien et al., 2018: ii).

There is broad agreement in the literature that social protection expansion should aim towards integrating individual programmes into a holistic state-led social protection system. Social protection systems figure prominently in the SDGs: Goal 1 to End Poverty, Target 1.3 calls for the implementation of ‘nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and vulnerable’.[4]

This move towards systems thinking has contributed to a large increase in the number of countries with a national social protection policy or strategy (ILO, 2017: 4). The ILO notes that ‘most countries have in place social protection schemes anchored in national legislation covering all or most policy areas of social protection, although in some cases these cover only a minority of their population’ (ibid.: 4).

However, extending effective coverage has significantly lagged behind legal coverage, primarily due to limited resources (ILO, 2018: 1), as well as implementation, coordination and capacity constraints (ILO, 2017: 4), and political factors. Many programmes for those living in poverty continue to be short term, delivered as pilot programmes for limited geographic areas, and lacking a stable legal and financial foundation (ibid.: 4; UN DESA, 2018: xxi). These contribute to improving beneficiaries’ situations but are less able to provide predictable and transparent benefits (ILO, 2017: 4).

Building social protection systems tends to develop progressively and sequentially (ibid.: 4). While there are many possible pathways to a comprehensive social protection system, many countries have introduced programmes in this order: employment injury; old-age pensions, disability and survivors’ benefits; sickness, health and maternity coverage; and finally, children and family and unemployment benefits (ibid.). In terms of population coverage, countries have tended to prioritise two groups ‘at opposite ends of the income scale’: introducing contributory social insurance for public and private sector employees; and establishing non-contributory (mostly tax-financed) social assistance to cover the needs of people living in poverty (ibid.).

Scale-up often means moving from donor-funded pilot schemes to formal adoption of the concept as public policy by governments, with recurrent costs covered by national resources (Ellis, 2012; UNDP, 2016: 74). However, many donor-funded demonstration initiatives have failed to transition to government-owned programmes (UNDP, 2016: 74). Some key considerations are for donors and government to collaborate in line with a country’s development objectives, identify national resources at the start of piloting social protection interventions; and support countries’ start-up costs of systemic social protection (ibid.). Donor funding can usefully be used to ‘monitor, evaluate, improve and scale’ government-driven programmes as well as ‘to establish and facilitate coordination mechanisms among government ministries, civil society and international and bilateral donors’ (ibid.). As scale-up is a political process, while the focus has tended to be on technical solutions, strategies to generate political will and commitment are important (IATT, 2008: 6). See Political economy.

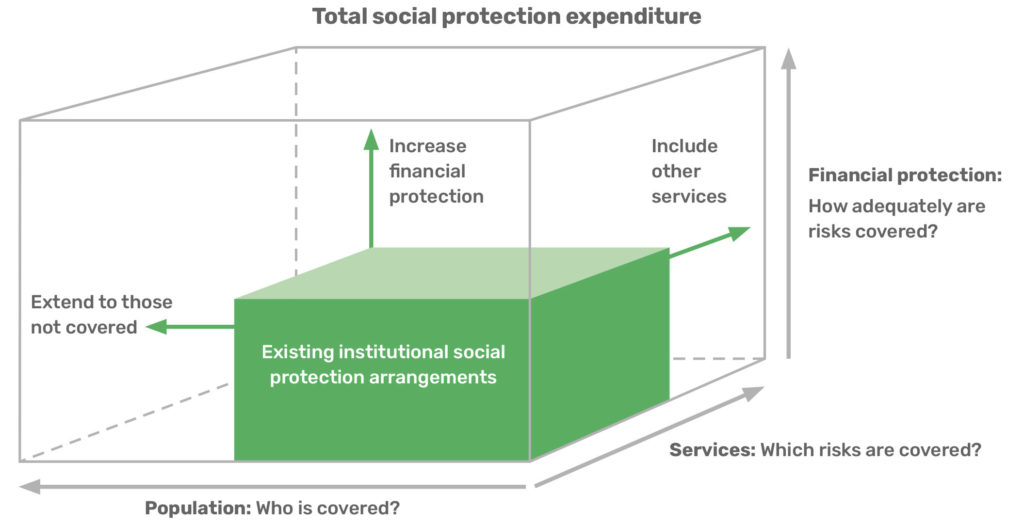

Given continuing social protection coverage and adequacy shortcomings, donors, agencies and governments are collaborating to support building inclusive social protection systems (ILO, 2017; UN DESA, 2018; UNDP, 2016). In 2015, the World Bank and ILO issued a joint plan of action on universal social protection (with the Universal Social Protection 2030 Initiative (USP2030) launched in 2016) to support nationally defined systems of policies and programmes that ‘provide equitable access to all people and protect them throughout their lives against poverty and risks to their livelihoods and well-being’.[5] See Analytical concepts. USP2030 partners aim ‘to work together to increase the number of countries that provide universal social protection’, including through ‘coordinating country support to strengthen national social protection systems, knowledge development to document country experience and provide evidence on financing options and advocacy for integrating universal social protection’[6]. Each national USP system will follow common fundamental characteristics (‘the need for equitable access, a nationally led approach and the capacity for expansion’) but each will be different according to national contexts, such as the existing level of social protection coverage and political and fiscal capacity to expand (Ulrichs & White-Kaba, 2019: 12). To facilitate progressive expansion to USP, social protection systems ‘need in-built flexibility’ (ibid.). Key questions on the way are: Who is covered (the breadth of coverage)? Which risks are covered (the scope of services)? Who pays for social protection and how much (the depth of financial protection)? (ibid.: 12–13). See Figure 3.

Figure 3. The USP cube: Progressive realisation of the three dimensions (policy choices) of universal social protection

Source: © Ulrichs and White-Kaba (2019: 12), reproduced with permission.

Key texts

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA). (2018). Promoting inclusion through social protection. Report on the world social situation 2018. United Nations.

This report looks at the contribution of social protection to social inclusion for seven, often disadvantaged, groups: children, youth, older persons, persons with disabilities, international migrants, ethnic and racial minorities, and indigenous peoples.

World Bank. (2018b). The state of social safety nets 2018. Washington, DC: World Bank.

This report examines global trends in the social safety net/social assistance coverage, spending, and programme performance, based on the World Bank Atlas of Social Protection Indicators of Resilience and Equity (ASPIRE) updated database. The report documents the main social safety net programmes that exist globally and their use to alleviate poverty and to build shared prosperity. It focuses on the role of old-age social pensions, and what makes social protection systems adaptive to various shocks.

ILO. (2017). World social protection report 2017–19: Universal social protection to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: ILO.

This report provides a global overview of recent trends in social protection systems, including social protection floors. It presents a broad range of global, regional and country data on social protection coverage, benefits, and public expenditure. Following a life cycle approach, the report analyses progress on universal social protection coverage with a particular focus on achieving the globally agreed 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

UNDP. (2016). Leaving no one behind. A social protection primer for practitioners. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

How can social protection play a transformative role to address the structural constraints impeding sustainable development and support the achievement of wellbeing for all? This primer is a practical resource on how to strengthen social protection to address the systemic and interlinked objectives of the sustainable development agenda. It provides guidance on how social protection systems can strengthen coherence among economic, environmental, and social objectives, and how to embed social protection into governments’ priorities and programmes.

See also:

Global Partnership for Universal Social Protection (USP2030). (2019, 5 February). Together to achieve universal social protection by 2030 (USP2030) – A call to action. Geneva.

Beegle, K., Coudouel, A., & Monsalve, E. (Eds.). (2018). Realising the full potential of social safety nets in Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Garcia, M., & Moore, C. (2012). The cash dividend: The rise of cash transfer programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Other resources

Conference/seminar/webinar: Building universal social protection systems. (2019). High Level Conference of the Global Partnership of USP2030. (1hr:10:44)

[1] Downloaded 5 June 2019.

[2] Sometimes studies include social pensions as one type of unconditional cash transfer; other studies put social pensions in a separate category from unconditional cash transfers. This report has tried to make the definitions used by each study clear, where studies provide the information.

[3] ASPIRE: World Bank Atlas of Social Protection Indicators of Resilience and Equity.

[4] https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/ (Accessed 9 April 2019).

[5] Universal Social Protection 2030 website: https://www.usp2030.org/gimi /USP2030.action (Accessed 4 March 2019).

[6] Ibid.